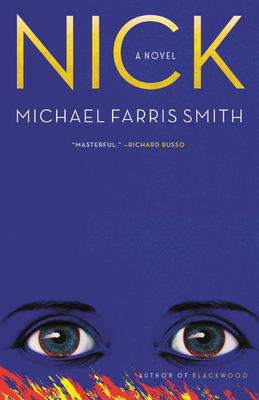

Book Review: Nick by Michael Farris Smith

The Great Gatsby, written by F. Scott Fitzgerald and published in 1925, is widely considered one of the greatest novels ever written. Its complex and thought-provoking depiction of New York City in the roaring twenties has riveted generations of readers and inspired films, parties, and Falcon opinion articles. On January 1st, 2021, more than ninety-five years after The Great Gatsby’s original release, the book’s copyright expired, opening up one of America’s literary paragons to free adaptation.

Michael Farris Smith, a former finalist for the Southern Book Prize, seized this opportunity and released Nick, his prequel to The Great Gatsby, on January 3rd. Nick follows narrator Nick Carraway from World War I era France to New Orleans as he struggles to find motivation and purpose through war and trauma. This story offers a fresh perspective on one of literature’s most mysterious “objective” characters, artfully combining the original novel and historical events to create a compelling novel in its own right.

Nick opens in Paris, where the title character and his lover, Ella, enjoy a brief leave from action. The first section of the novel alternates between Paris and the front of World War I, where Nick experiences intense isolation and depression. In both locations, Nick cannot remain in one place for more than a short time; he sometimes abandons Ella to go back to the front before his leave ends, and he frequently accepts dangerous and optional relocations in the military.

After an especially harrowing brush with death while at war, Nick escapes the conflict and decides to return home. This choice, like all of his decisions in Nick and Gatsby, is made rashly and solely on gut instinct. Once Nick arrives in Chicago, he immediately resolves to take a train to New Orleans in order to avoid seeing his family once again. This trip initiates the great adventure of the book, in which Nick navigates violent saloons and unsavory characters in order to support a fellow ailing veteran.

Although Nick is independently an engrossing novel, it is most interesting to readers as a companion to Gatsby, investigating the cryptic life of Nick Carraway to a previously unmatched extent. Both sections of the book are peppered with flashbacks that narrate Nick’s early life, and although they are not canon to the Gatsby universe, the fascinating scenes explain many of Nick’s actions in both books. The flashbacks, coupled with scenes on the battlefront in France, essentially argue that Nick’s vigilant and taciturn character is significantly attributable to PTSD from both the war and complicated and unacknowledged family trauma.

Smith’s interpretation of Nick Carraway often corresponds to Fitzgerald’s, although some scenes are hard to reconcile with the original. Whereas Fitzgerald’s Nick resists advances from Jordan Baker and generally avoids romance, Smith’s is almost obsessed with women during his time in Paris. Smith’s account also ascribes to Nick a level of empathy and passion that doesn’t exactly hold up to readers’ prior understanding. Overall, though, Nick’s protagonist is generally squarable with The Great Gatsby’s narrator — his simultaneous external reticence, judgemental internal monologue, and vapid listlessness are evident and character-defining in both novels.

Jay Gatsby, the protagonist of The Great Gatsby, is never mentioned in Nick, but Smith gives him a clear foil. In New Orleans, Nick encounters Judah, a fellow veteran fighting addiction, a violent streak, and the demons of war. Judah returns from the war to find the life he left in a state of total disarray, triggering a messy, tragic, and long-lasting conflict with his ex-wife Colette, who also plays a prominent role in the story. Despite these red flags, Nick develops an unshakable loyalty toward Judah, defending his friend even when it puts his own life in danger. This storyline can be easily construed as a justification of Nick’s tragic undying support for Gatsby in The Great Gatsby.

Despite having been raised in different areas and socioeconomic circumstances, Nick and Judah find common ground in their difficulty to resettle in the United States after the war. Smith describes this struggle, the central theme of the novel, as “hiraeth” — in the epigraph, a hiraeth is described as “a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, a home which maybe never was; the nostalgia, the yearning, the grief for the lost places of your past.” Through telling Nick’s and Judah’s stories, Smith argues that the war generates the chronic loneliness that defines Nick’s character in The Great Gatsby.

Nick is a novel, but its meticulous account of life on the battlefront and the chaos of prohibition-era New Orleans is well-researched and imparts the reader with newfound historical knowledge. Its omission of race-related commentary and acknowledgment of characters’ races in poorer sections of early-20th century New Orleans is its primary flaw when it comes to historical accuracy.

It would be deeply unfair to Michael Farris Smith to evaluate Nick exclusively in its comparison to The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is the perfect novel: concise, captivating, inventive, and rich. Nick is a worthwhile read in its own right — packed with historical intrigue, thrilling storylines, and rapid plot twists, it is a great gift or purchase for any Gatsby lover.

Score: 3.5/5