How Has Social Media Transformed American Politics?

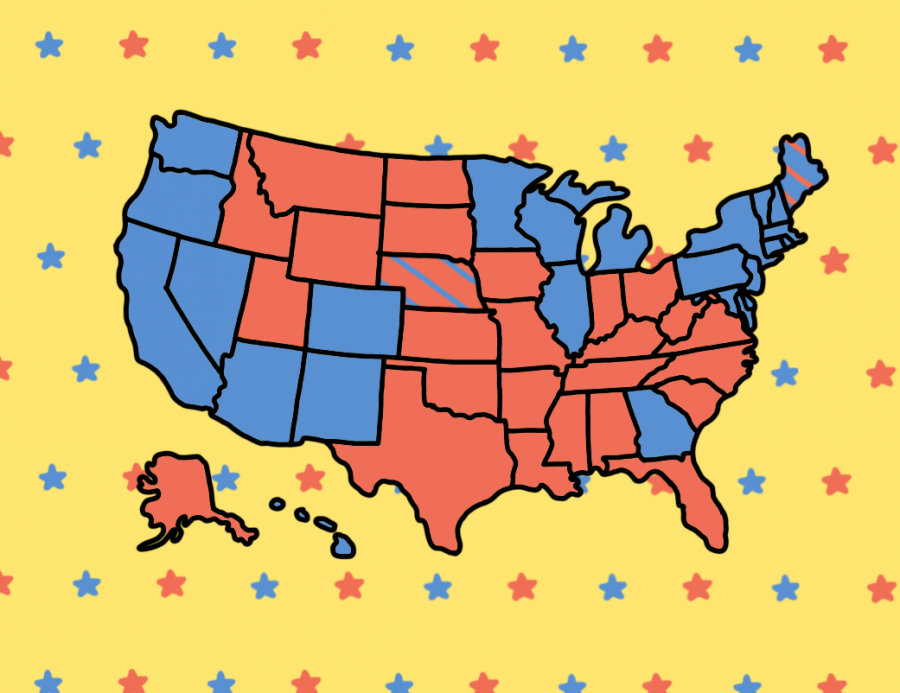

This illustration by photographer Annie Rupertus ’21 represents the 2020 Presidential Election. The color-coded states show the Electoral College results. This image was made using Autodesk Sketchbook.

Since the turn of the 21st century, social media has become a hub for entertainment, communication, and pop culture. More recently and controversially, it has also become a forum for politics. Former President Donald Trump, named by The New Yorker as the “internet’s candidate,” completely redefined the use of social media for political content in recent years.1 2 He used Twitter, in particular, to develop and maintain a personal connection to his supporters.3 By the end of his term, he averaged “986 tweets and retweets a month.”4 The recent and growing presence of political content on easily accessible social media platforms has radically transformed the political dynamic in the United States.

Echo Chambers, Algorithms, and Artificial Intelligence

One phenomenon often associated with the politicization of social media in recent years is the concept of the “echo chamber:” an “environment in which a person encounters mostly beliefs and opinions that support and reinforce their own… while alternative ideas are largely absent or ignored,” as Toronto News puts it.5

Dr. Megan Boler, a professor at the University of Toronto in social justice education, says “[echo chambers] are reinforcing what we’ve told them about ourselves until we are a more rabid version of ourselves,” contributing to the polarization of the United States.6 This, in turn, can influence how people vote and popularize having extreme political opinions on either side of the spectrum.7 Social media is making it increasingly challenging to see other points of view and to solve political conflict across party lines; it is posing as a challenge to American democracy.8

The primary way echo chambers are created is through algorithms, which are “coded instructions that automate the platform’s functions to filter the content users see” by reading trends of what content they tend to interact with.9 Eli Pariser, the CEO of Upworthy, says that algorithms hook users in to boost engagement and, in turn, revenue.10 11 Users also do have some level of control over their digital environment, in that they can stay offline, unfollow people, or intentionally read content of differing viewpoints.12

Dr. Jaime Settle, a professor of government at William & Mary and the author of Frenemies: How Facebook Polarizes America, explained this phenomenon further in an interview with The Falcon, saying: “Algorithms exacerbate human psychology. People say that they want moderate, fair, balanced content from diverse sources, but what they actually click on tends to be content that they agree with or that is shared by people that are friends with them and that they probably agree with. Algorithms are only making clear what our own preferences are… I think algorithms in that way are making the problem worse, but people are still being exposed to diverse content. I think there is a misperception that they keep people completely in echo chambers, and that’s just not the case,” she says.13 14

However, algorithms do come with a downside. The programmers who write algorithms can unintentionally factor in their own biases, claims CBS News.15 Algorithms treat all people (the very privileged, the oppressed members of minority groups, and anyone in between) alike; in turn, sensitive activism content can easily be censored because artificial intelligence regulates the platform and enforces “community standards” which don’t process intention or context.16 Mark Luckie, a digital strategist for Twitter and Facebook, explains the technology industry is largely made of “white and Asian males, and so what happens is the opinions, the experiences that go into this decision-making are reflective of [that] group… people from different backgrounds — Black, Latino, different religions, conservative, liberal — don’t have the accurate representation that they would if these companies were more diverse.”17

Echo chambers are driven by a construct called ‘confirmation bias,’ defined by GFC Global as “the tendency to favor info that reinforces existing beliefs.”18 This makes it difficult for people to have complicated conversations and even to process differing viewpoints. Though this can occur both in face-to-face conversations and online, it can happen quite easily on the internet because of the wealth of social media platforms, news sources (both reliable and unreliable), and spaces on which one can share opinions.19

According to GFC Global, echo chambers are not only easy to manufacture, but they are difficult to recognize because of how natural it feels to be surrounded by people with generally similar opinions.20 Participants must look for multiple news sources, objective information, complete evidence, and multiple viewpoints in order to attempt to avoid these chambers. All of this, though, does constitute a fair amount of burden for average readers who may easily and unintentionally fall into extreme echo chambers without a high level of digital awareness.

Youth and Social Media

Another contributing factor to the politicization of social media is the increasing presence of younger users. According to a 2018 Pew Research Center study, 95% of teenagers either own or have access to a smartphone, which is a 22% increase from a similar 2014 survey.21 Furthermore, “45% of teens now say they are online on a near-constant basis.”22

A study from the British Journal of Politics and International Relations finds that social media acts as a tool for young people to access political content.23 It allows “citizens to look beyond the established political institutions to find new and creative ways to express their political preferences and to achieve their civic and political goals.”24 Common examples include “protests, petitions, boycotts, and models of engagement (such as social media campaigns).”25 The internet has increased access to information and content; diversified the range of available information which in turn increases “the number of viewpoints available to citizens;” increased the rate at which information can be shared; allowed regular people to seek out their own news and create their own content so they are no longer reliant on “institutionalized media;” allowed individuals to become “creators of web content… [rather than] passive consumers;” helped people “locate like-minded individuals [and] convey their own messages;” and allowed people to become “actively involved in their fields of interest.”26

According to the aforementioned study, even if individuals do not become writers and creators themselves, the digital environment can still induce political thought and participation.27 This can occur through increased exposure, seeing friends and family post and promote information and opinions, and can in turn, “trigger political interest… or social pressure to become engaged.”28 Even non-political online spaces can “provide a pathway to participation in volunteering, protests, and political voice.”29

This study also explored the use of the internet as compensation for young people, being that they are usually not able to engage politically because they are enduring the traditional life steps like “education, finding employment, and completing the transition to adulthood.”30 While younger people have fewer resources like “time, money, [and] mental energy” at this phase of their life, an online presence “requires fewer resources… and has suggested that [it] could compensate for the resource limitations that young adults face and provide a low-cost site for engagement.”31 This allows people to engage with political parties, find information about voting, and more.

Misinformation, Disinformation, and Fake News

Other important components of political social media are misinformation, disinformation, and “fake news,” a famous term coined during the Trump era. With an increased presence of younger users on new platforms, many readers may not have the digital literacy skills or social media experience to consistently identify reliable sources. The University of Washington library explains: misinformation is false information that has been circulated, regardless of intended impact; disinformation is intentionally bias and misleading information, or propaganda or fake news is “purposely crafted, sensational, emotionally charged, misleading or totally fabricated information that mimics the form of mainstream news.”32 Fake news can also “[inflame] or [suppress] social conflict,” according to the UC Santa Barbara Center for Information Technology and Society.33 Not only does it instigate conflict, but it also “undermines people’s faith in the democratic process, people’s ability to work together,… their ability to participate in governance of their country, [and their ability to] make important decisions regarding the fate of their nation.”34

Although flawed content poses an issue for everyone, opinions on how to deal with it differ by party. Dr. Settle explains that Democrats and liberals are more concerned with the removal of fake news and hate speech, where Republicans and conservatives prefer to have less control. Specifically, sites like Parler and Gab emphasize their intentional lack of regulation and control.

Dr. Settle also explains that political affiliation is no longer just a set of opinions or preferences; rather, it is more of a social identity that is largely recognizable by the general public with external indicators like style or music taste. “When political scientists think about what people mean when they say they are a Republican or a conservative vs. a Democrat or a liberal, for a long time, scholars disagreed about whether that meant that they agreed with the policies of that group or whether it meant that they saw themselves as a member of that group. The answer is that in different areas of American history, it meant different things. Now, what we think is going on is that these labels refer to identities. That people think of themselves as being members of a group and that the connection they feel to their party or ideology is not necessarily because they really strongly share the policy preferences, it’s because they look at the group and have a reinforcing sense that people like them are members of that group,” she says.

Censorship of Free Speech & Expression

On January 9th, Twitter controversially banned former President Trump’s account, leaving 88.7 million followers without their ringleader.35 In addition, Amazon Web Services withdrew its position as a platform host to Parler, a largely conservative Twitter alternative.36 While some believe that social media censorship is a government restriction of the free speech guaranteed by the First Amendment, it actually comes from the companies themselves, and cannot be classified as a federal control.37

This illuminates the long-standing clash between social media platforms and the right to free speech. Although historically, the left has been more supportive of freedom of speech, their stance on the issue in specifically a social media context has flipped, now supporting harsher regulation, and vice versa for the political right. “Neither [party] has had to confront taking their argument to the logical extreme… both sides are going to run into a wall at some point where their views are challenged,” she says.

Section 230 and Legal Regulation

As part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, the U. S. Congress passed Section 23o, a piece of legislation stipulating: “No provider or user of any interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”38 This essentially means that online platforms are the ‘host’ of their content, but are not the providers and therefore not legally responsible for harmful information, acting as an “online service that publishes third party content.”39 Section 230 is named “perhaps the most influential law to protect the kind of innovation that has allowed the internet to thrive since 1996.”40

Dr. Settle names Section 230 as a “fuzzy legal situation” that “protects companies at large on the internet (including social media platforms), [giving] them permission to remove things from their sites but also [protecting] them from not removing things from their site.”

“Some people make the argument that [social media platforms] have become the digital public sphere, and the decisions they make have the consequence of limiting people’s speech… most platforms have come down on the side that they remove hate speech, they try to remove bullying, and misinformation varies platform to platform depending on what they define as misinformation. It is right now largely guided by internally what the companies want to do instead of a strong legal framework,” says Dr. Settle.

Section 230 includes a “Good Samaritan” protection for blocking offensive material.41 This essentially protects social media platforms’ ability, “in good faith, to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected,” as Cornell Law School puts it.42

While this may seem beneficial, it has proven quite controversial in an exceedingly political, polarized, and divided country. A 2020 Pew Research Center study shows that “today, 69% of Republicans and Republican leaners say major technology companies generally support the views of liberals over conservatives,” whereas only a quarter of Democrats and Democrat learners back this statement.43

The “Alt-Right” and Political Extremism

Some conservatives end up on “alt-right” sites like QAnon, Parler, and Gab, propagating false information, promoting white nationalism, and subscribing to shocking conspiracy theories. One in particular — the QAnon conspiracy theory — narrates that “the world is run by a Satanic group of pedophiles that includes top Democrats and Hollywood elites, and that President Trump has spent years leading a top-secret mission to bring these evildoers to justice.”44 According to a profile of a QAnon “digital soldier” in the New York Times, the main attraction of the conspiracy isn’t the shocking beliefs, but rather, the “community and sense of mission it provides,” the entertainment, the online-game quality (with strong communal participation), the ‘religious’ qualities (generating a following and a social support with an “organizing narrative for their everyday lives), and the alternative-reality virtual fantasy world that it creates.45

Alt-right sites also played a vital role in the Capitol insurrection on January 6th, providing a platform to coordinate efforts.46 New York Times journalist Stuart Thompson found his way into a QAnon chat room for three weeks — from before the riot until after the inauguration — and recorded his disturbing experience.47 Participants continually ignored the truth, “fact-checked” sourceless information with one another, commended their fearless leader Trump, called for the public execution of Vice-President Mike Pence, and praised the Capitol violence, calling the scene “patriotic” and “beautiful.”48 The author writes that believers take the approach to interpreting news of finding information to “confirm any existing beliefs” and using it to fit their conspiracy narrative, which may include rejecting conflicting facts.49 This then leads to struggles in their personal lives, in that users may struggle to connect with and recruit family members using half-proven political claims.50

After President Biden’s inauguration, Thompson noted that QAnon supporters did not abandon their beliefs or back down. Instead, they invented a new narrative, claiming that they had been misled by fake news and “misinterpretations.”51 They responded by developing new sources, “inventing journalism,” and emerging with a strong sense of unity and power.52 Their community bond was, in fact, so strong that many members were “shunned by friends and family” due to their dedication to their chat-room peers.53 The author notes that “beneath the anger in their voices is often pain or confusion,” resulting in members sharing their social or economic struggles and vulnerabilities.54

Despite how shocking some of the claims and beliefs of ‘alt-right’ chat members are, in their minds, they are not ‘extreme’ or even out of the ordinary. “Everybody thinks they are moderate. Everyone thinks that their views are in the middle and the majority,” says Dr. Settle. “I’m guessing that a lot of people in what most Americans consider the ‘alt-right’ — they think they are the majority. If you get on Parler and hear what they are saying, they think they represent what most Americans support.” Although Dr. Settle says that the ‘alt-right’ is difficult to measure in size, especially because it is largely an online presence through unregulated conservative sites, a New York Magazine study estimates that roughly 24 million Americans have “alt-right beliefs.”55

*************************

Social media has clearly taken on a new political identity in recent years. The effects span beyond a virtual reality: they change people’s identities, radicalize their opinions, and polarize the entire nation. From echo chambers to algorithms, policy opinions to entire social identities, confirmation bias to conspiracy-believing communities, social media has become central to American political culture.

What does this mean for the future of the country? Is this transformation hugely worrisome and in need of repair? Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem that meaningful and immediate reform is possible due to the increasing expansivity of the internet. To me, the politicized and radicalized state of social media is truly telling of the Trump era. A presidency that introduced so much hate and division is sure to have far-ranging tentacles that pollute all aspects of American life. Of course, that is exactly what it did, strangling people into echo chambers and brainwashing them with extreme views that may not really be their own. For better or worse, essentially everyone uses social media to some degree. I hope that sites implement reasonable regulation of hateful and misleading content and that technology education at a young age breeds healthy digital awareness and acknowledgment of one’s own biases. Social media is not going anywhere anytime soon; we might as well use it as a tool to educate, connect, and express political views in a passionate but healthy way.