The Impact of Covid-19 on Learning and Well-Being

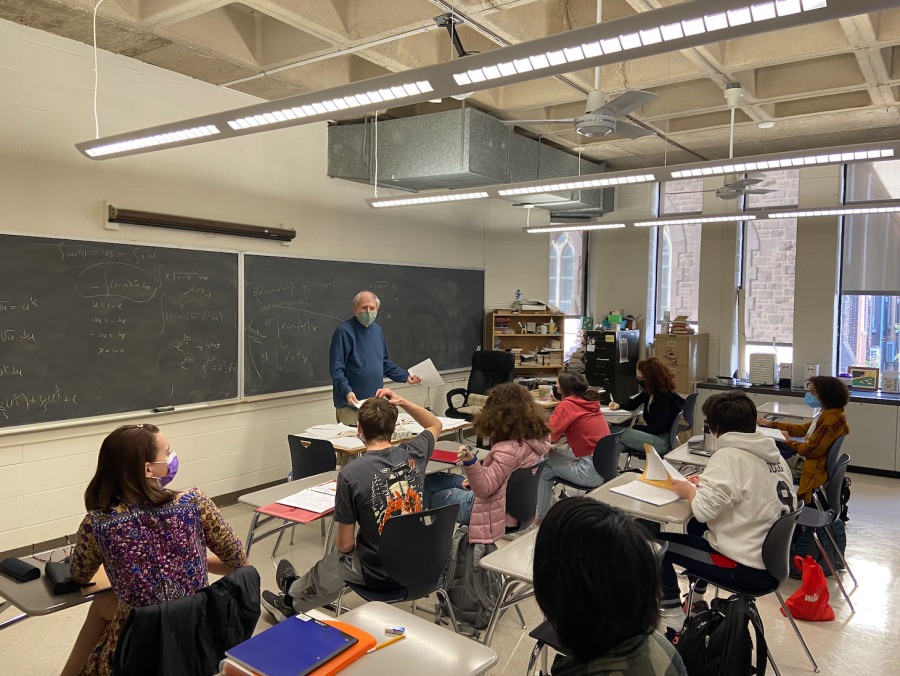

Advanced Calculus Class.

A year ago, students took classes from their bedrooms. They could position themselves comfortably, manage their schedules individually, and learn from the comfort of their homes. Now, while students sit in class, some struggle with shortened attention spans and find schoolwork extremely difficult to manage. They bring these stresses back to their homes, where they find that they no longer can study productively or focus for periods of time. The lingering tentacles of a year and a half of pandemic-style learning continue to discourage and overwhelm many students these days.

The abrupt difference in the pacing of the school year virtually vs. in-person is one of the main challenges that students face. Ava Liddy ‘22 notes the frustrations she faces from not retaining much of the information she learned and processed last year, and is grappling with how to move forward and establish effective studying tactics for difficult classes. “How do I go back and review that [material from] last year and build off of it in the three hours of study time for a test?” she inquires.

An Upper School survey from The Falcon shows that out of 83 responses, more than 72% of students felt that they have needed to change or adapt their study methods from previous years to the learning style and pace of the current Friends Select environment.

Rose Levine ‘24 notes that she feels that some sort of easement into this faster-paced, rigorous year would have been helpful for her. She finds herself procrastinating frequently because she is no longer able to self-dictate the structure of her day. Another shift Rose notices in her learning tendencies is: “I get distracted very easily by being around more people, but I also [appreciate] being in the classroom and learning, so I [am] more focused [in class].”

The change in physical learning setting was more challenging for some than others. Lily Brin ‘23, a student who was completely virtual for last school year, says, “I was just able to turn off my [mic] and sit in my chair however I wanted to. I was behind a screen and I could do whatever I needed to do… this year, I just can’t do that.”

Students acknowledge that the jump in two grades over the pandemic period contributes to the myriad shifts in rigor and difficulty with the workload. “I think this shift [in pace and difficulty of her classes] might have to do with the change in my grade, but also such different circumstances from last year… the expectation was much lower, and now all of the sudden, it’s full and high,” Rose says. Lily agrees, describing the jump as “unimaginably difficult for [her].”

The aforementioned Upper School survey shows that more than 57% of respondents also feel that the transition into this year was abrupt and difficult for them to manage.

With this brief and challenging transition, some students are experiencing severely waning attention spans and trouble studying; they point to a few tangible examples of these effects. Ava describes a recent night in which she studied for an Advanced Physics test, explaining: “I went through everything and retained nothing. Just studying has become so much harder.” Lily agrees, noting that it takes her much longer to actually grasp new material.

Rose adds that she does not remember her study methods from previous years, so “actually [comprehending] the right information and staying focused” is tedious, making it difficult to feel prepared for assessments.

The student survey reflects this sentiment: more than 77% of students felt that their attention spans or ability to focus have been affected since the pandemic.

With new material being presented at a pace that feels rapid and overwhelming for some, students now feel a responsibility to supplementally teach themselves the material in order to keep up. “I’m having to do a lot more learning of the material outside of class, and I think that’s harder for me to do because it’s like I’m teaching things to myself,” says Lily.

In the survey, students were asked how manageable their workload is this year on a scale of 1-5, with one being ‘totally manageable’ and five being ‘not at all manageable.’ Over 50% responded with a 4 or a 5 on this scale.

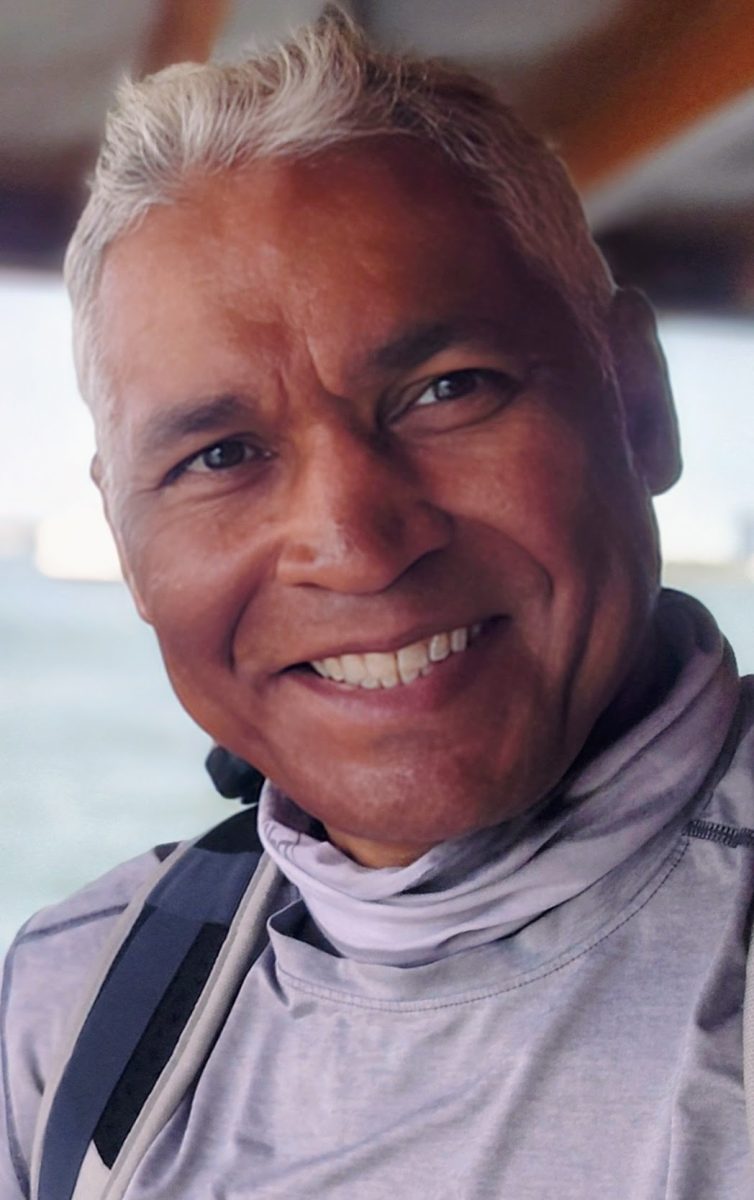

What students are facing in relation to their focus, studying habits, and workload is a larger phenomenon than the strictly academic aspect of being a student. The pandemic has impacted students’ emotional and psychological wellness as well, explains Dean of Students Norman Bayard. “I’m noticing that students are tired, students are overwhelmed… it’s draining a lot of people. It’s draining our minds, our bodies, and our spirits.” Norman acknowledges that there are myriad adjustments that both students and teachers and Friends Select have to make, “especially when you’re talking about adolescents and development, things that you have to contribute to maturity.”

Students finding their priorities, as Norman notices, has become challenging to do. “What I’m going to say is this: your #1 priority is you. Take care of yourself… why does our self-care have to be an afterthought? If we don’t take care of ourselves, what good are we?” he inquires. Some students, he notices, are intentionally putting themselves first and doing things to “ease [their] minds and souls;” this self-prioritization may entail falling behind on homework in the rigorous college-prep environment. Other students, though, are developing unhealthy habits to cope, including “heavy caffeine consumption.” Norman strives to prioritize activities to bring spirits and morale up, such as spirit activities, “moments of wellbeing,” and club events. However, “are clubs becoming a job for some people? Especially those club leaders and organizers?” he wonders.

Although the complexities of this post-pandemic brain fog are quite evident within the school community, they extend far beyond the bounds of Friends Select. “People are losing the physiological, social, and emotional resources that we use to meet the demands of our daily lives,” says Anthony Wheeler, Dean of Widener University’s School of Business Administration. “The lack of focus [that many] experienced during the past year stems from both physical and psychological factors, such as noise, interruptions, multitasking, isolation, and the loss of healthy routines,” claims the Washington Post in an article naming some causes to these widely observed effects.

A cognitive research journal study from SpringerOpen, a portfolio of open access to peer-reviewed pieces of science and medicine research, discusses some of the neuroscience aspects of the aforementioned “mind-wandering” and attention issues. “Increasing evidence has shown that internal states, including ongoing worries, interfere with attention… when occasional thought probes are used to access the focus of one’s thoughts during a continuous task, participants often report task-unrelated thoughts that are grounded in their concerns,” it states. The study also explores the impact of emotions, like fear, in attention span: “compared with neutral stimuli, fearful stimuli tend to capture attention.” This includes the fearful and stressful feelings and stimuli that have become routine throughout the pandemic year.

Whether the causes are increased pace and difficulty of schoolwork due to a 2-grade jump or the lingering mental and emotional effects from the pandemic, students offer some suggestions on what they imagine teachers can do to reduce feelings of burnout and anxiety surrounding their school experience. Rose requests that teachers try to gauge how many major assignments students have at a certain time, and be conscious to spread them out over separate weeks. Lily adds, “there will be nights where I have zero homework and there will be nights where I have all of the assignments in the world. I think teachers making their assignments more evenly spread throughout the week making the course load a bit lighter would help a lot.”

Mark Schneider • Nov 10, 2021 at 4:59 PM

Thank you for your articulate presentation of the challenges of being a high school student in these trying times.