Blood Quantum and What it Can Mean to Indigenous People

Imagine having an official card or document that states what race you are and the specific percentage of blood you have for that race. Despite what you identify as, this information on this card, or even not having one, could be the deciding factor in how others perceive you. This may seem strange, but it is normal for Native people.

Growing up, being Native was always part of me, and I didn’t really question what it meant or exactly how being Native was defined. Recently, I have become interested in blood quantum and how being Native is defined by others. I remember during Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign, she claimed to be Native, which caused some outrage because many said she had no ties to the tribe she was claiming to be connected to. There are many instances of people trying to police identities and call out others that they think aren’t “real” Natives.

“Blood quantum” is the percentage of Native or “Indian” blood someone has. The idea was originally introduced by the federal government and it limited tribal citizenship. To be enrolled in a federally recognized Indigenous tribe, there are certain blood percentage requirements. The requirements can vary, and some tribes have moved away from using this system.

Laws and ideas that define race for the benefit of white people have been around for centuries. An early example of this in America was the Virginia colony in 1705. Racism was obviously around, but there were inconsistencies in how different races were defined by law. A person would be completely considered Black if they were just ⅛ Black, and therefore would have no civil rights and could be enslaved. In contrast, someone would have to be ½ Native blood or more to be considered Native. If they were less than half, they would not be considered Native and could lose rights to the land set aside for them. Expanding the definition of Black, and having more people who fit the legal definition of Black, meant more people that could be enslaved and exploited. Restricting who was defined as Native allowed white people to take over their land. I feel it’s very clear that white people shaped these definitions in order to maintain power and control.

Throughout US history, the government has stolen from Native people and tried to assimilate them. One way in which they did so was was the Dawes Act in 1887. The Dawes Act allowed the government to break up tribal lands and divide them into individual plots, which were given to individual Native people. Whether they got the land allotment depended on if they had enough blood to be considered Native or not. This excluded people that were mixed and didn’t have a high enough Native blood percentage, but were still affiliated with the tribe. There were many Black Natives that had been living culturally as members of a tribe, but were denied land because they technically lacked the blood requirements. This was what the government and white people wanted because it allowed them to keep more land for themselves, reducing Native territory. Theodore Roosevelt referred to land allotment as “a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass.” About 90 million acres of tribal lands were taken by the government through this act (keep in mind much had already been taken before this). This further shows how bending the way race is defined benefits the white government’s agenda. What it also did was racialize groups of people that were defined by much more than just race. It wasn’t until 1934, after the Indian Reorganization Act, that tribal governments were allowed to exist again, ending the Allotment Era.

Blood quantum is still used today and can be controversial among Native people. The Bureau of Indian Affairs uses the certificate degree of Indian blood to decide who is eligible for federal social services. Tribes can now choose their membership requirements; many use blood quantum, but it can vary. The Navajo Nation has 25% as the requirement, and Turtle Mountain Tribe requires 25% of any Native blood as long as any of that 25% is Turtle Mountain. These are calculated using tribal documents by tribal or government officials, using the original rolls.

Some Native people are in favor of strict blood quantum requirements because they believe that it is a way of preserving Native culture and keeping communities tightly knit. They are concerned that opening up enrollment will allow people to falsely claim they are Native in order to take advantage of tribal benefits and services. The main issue with blood quantum today is the exclusion of people that are mixed, adopted, or simply not enrolled but have cultural and community ties. Some people are concerned about their descendants not being able to enroll and eventually losing touch with their culture. Some people have rights to land, but a few generations down, their children will no longer own the land. Doing the math, if someone that is only 25% Native has a child with a non-Native, their child would not be able to enroll in the tribe (depending on the tribes’ requirements). This can lead to pressure among Indigenous people to marry within their race/tribe.

I spoke to Colleen Farwell, from the Crow Nation, about her opinions on blood quantum. She is not in favor of it. “It’s effective in what it does, but it’s not representative of Native people… our societies and nations were based on kinship… if someone came from other nations or other places and married in, [they would become] part of society,” she explained. A specific thing I was curious about was why many tribes and people are still in favor of keeping blood quantum around. “I think it’s fear,” she said. “And the federal government has instilled that fear.” She went on to explain how where she is from, if the tribe has sales from their natural resources, everyone gets annuity checks a few times a year. They could be $100-$500 each. “I think a lot of people are thinking, ‘if we have more people, we’ll get less money each.’” Some people are worried about losing out on federal benefits. However, Collen thinks that we need to look at the bigger picture. “If we don’t figure out the situation and come back to our original ways of being… we’re gonna disappear. What good is it being the last one standing and having all the things, but you’re only one?”

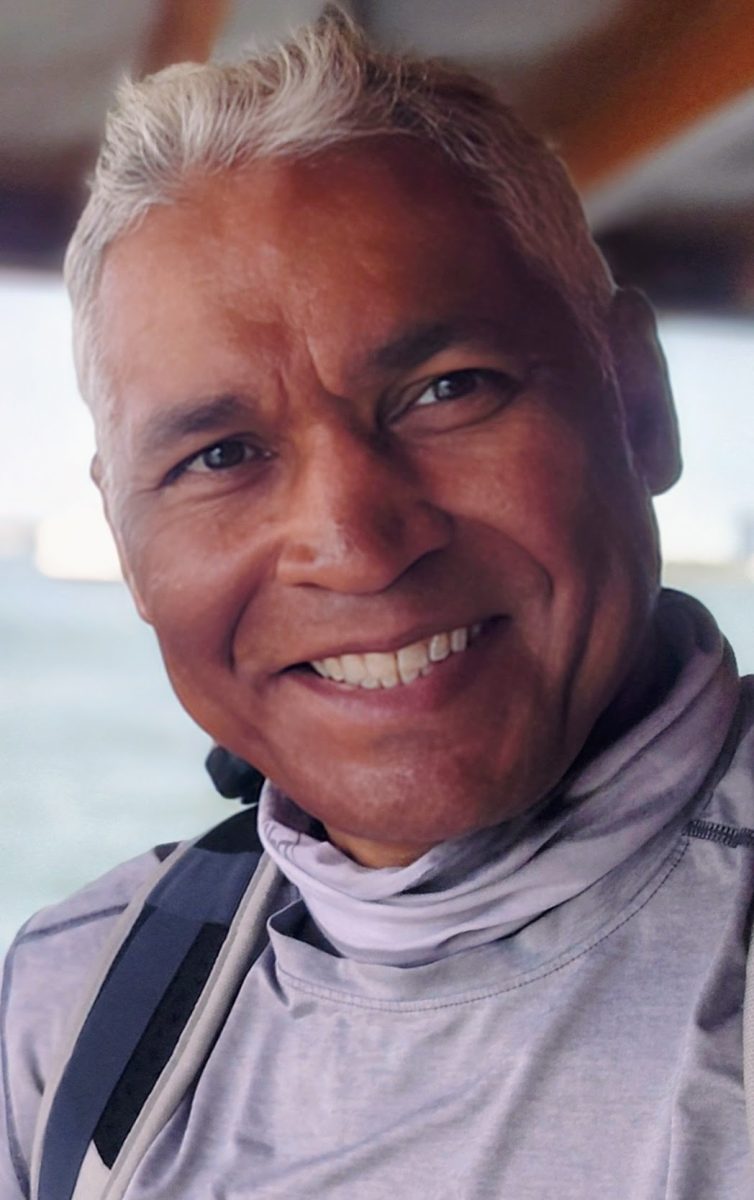

As a Native person who is mixed, I’m not too concerned about being only part Native or my exact blood quantum. I am an enrolled member of Ohkay Owingeh. I grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, not far from where the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo is. My father’s family is from there, and it is where he grew up. I’ve spent lots of time at the reservation and participated in many cultural events. My kinship and cultural involvement hold more weight in what being Indigenous means to me, rather than just the specific blood percentage.

The issue of keeping blood quantum, or not, is tricky. On one hand, it’s now the tribes’ right to determine their rules for citizenship and they should be able to maintain that ability. But, thinking ahead, what will happen in a few generations, when people have mixed children and blood percentages become lower? Not everybody is going to marry within their tribe. Eventually, there could be fewer Native people, leading to loss of culture and the government claiming more land. A nation can’t exist without its people. I think that for the survival of our people and cultures in the future, a change will be needed.

Gardner Dunne • Jan 9, 2024 at 4:14 PM

i think this is such a helpful article. Thank you

Simone Dashiell • Feb 23, 2023 at 2:03 AM

What are some of the reasons that tribes still use blood quantum?

Andy M • Feb 2, 2024 at 5:41 PM

The Federal government only recognizes 25%. So when lowering your standards or doing away with those standards.. puts a strain on funding from the government because your only funded for a blood quantum of 25% Native American.. so then some of your funds are going to someone who might just be a descendent and most tribal governments have seen the same amount of funding for the last 10 or 15 years.. Thank god for Grants.. or thank the government

Dave Marshall • May 21, 2022 at 7:56 AM

I learned so much from this article – thanks for sharing! Will definitely use in my U.S. History classes moving forward.