Opinion: Is It Acceptable to Mock the Deaths of Evil People?

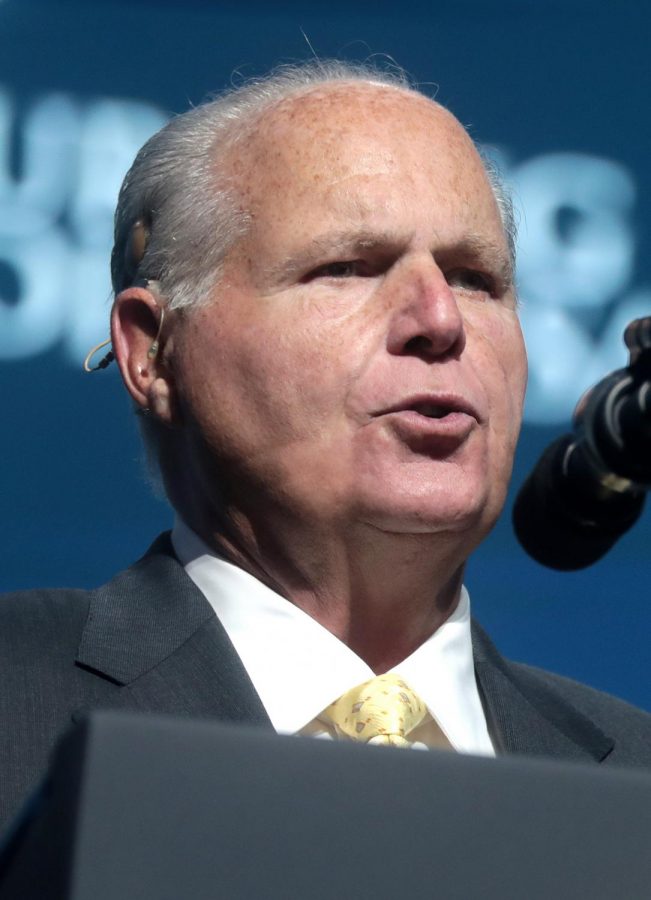

The death of prominent radical conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh on Wednesday, February 17th drew polarized responses across the United States. People and organizations affiliated with the alt-right like former President Donald Trump, Breitbart, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis praised Limbaugh’s contributions to the conservative movement. Conversely, liberal celebrities including David Cross, Bette Midler, and Ron Perelman rushed to celebrate Limbaugh’s passing, with Cross tweeting “cancer killed the cancer.”

Limbaugh rose to fame in the late 1980s when his daily radio talk show started broadcasting to national audiences. His listeners, mostly conservative, appreciated his brash, entertaining, and unapologetically offensive speech. Limbaugh lambasted the “liberal media establishment,” freely sharing his contempt for feminism, LGBT rights, and social justice initiatives that benefit the Black community. His success aided the Republican Party to their massive victory in the 1994 midterm elections and partially inspired the rise of Fox News. He was a frequent and prominent critic of President Obama, and later used his platform to campaign for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. For years, pundits have labeled Limbaugh as one of the most influential conservatives in recent memory.

Varied jovial responses to Limbaugh’s death sparked adverse reactions from many conservative news outlets and even liberal New York Times columnist Frank Bruni. In an opinion aired in the Times on Saturday, Bruni argued that “roughness certainly isn’t going to lead anyone to the light, and it may well encourage its targets to hunker down in their resentment, double down on their rage.” That is to say, the insensitivity of mocking death only further alienates the dead’s supporters. Bruni’s article, like many other critiques of liberal joy in the wake of Limbaugh’s passing, connects to a larger question about the morality of celebrating when people who many perceive as evil die.

In many respects, celebrating the deaths of enemies appears to be human nature. When Adolf Hitler died on April 30th, 1945, newspapers across the world responded with cautious, stifled optimism — “Germans put out news everyone hopes is true,” read the British Daily Express. Hitler is certainly an extreme example of an enemy, but this cheery attitude toward death has also followed the passings of significantly less evil characters: Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and Richard Nixon were all widely mocked in the days following their deaths. In 2011, Phillies fans at Citizens Bank Park responded to the breaking news of Osama Bin Laden’s death with a raucous “U-S-A” chant. Death-mocking has even appeared in entertainment aimed at young audiences — In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her companions famously celebrate the death of the Wicked Witch of the West by throwing a parade and gleefully singing “Ding-Dong, the Witch is Dead.”

These reactions, whether applied to horrific tyrants or fictional villains, are understandable. The mockery and celebration in response to the deaths of evil people are driven primarily by relief and excitement that those people can do no further harm to the groups they’ve hurt. In the same way that we respond to the deaths of our heroes with the same praise we offered while they were alive, we should take the deaths of maleficent figures as an opportunity to reflect on their negative impact and criticize their lives.

Even if mocking death is a somewhat natural response, it can still be inconsiderate and disrespectful in some circumstances. Limbaugh is survived by his wife, Kathryn Limbaugh, who will surely see others’ giddy tweets during her period of mourning. Even though Limbaugh never offered a shred of empathy to those who needed it most, two wrongs don’t always make a right, and some argue that poking fun at Limbaugh’s passing is just as bad as the treatment that he gave to others. This grey area is part of the reason why few liberal politicians celebrated Limbaugh’s death — if they spoke, they would be in big trouble.

Part of the laughable irony of Limbaugh’s death was the frequency with which he made fun of the loss of innocent lives. During the AIDS epidemic, Limbaugh aired a daily segment entitled “the AIDS update,” during which he read the names of gay men who had died over lighthearted background music. Additionally, he mocked Eric Garner’s brutal and unjust murder at the hands of police officers, saying: “I can breathe because I follow the law” and blaming his death on high cigarette taxes. He also satirized Michael J. Fox’s battle with Parkinson’s Disease, Kurt Cobain’s suicide, and many other tragedies. Thus, there can be no critique of those laughing at Limbaugh’s preventable demise.

Limbaugh’s family and friends may be mourning the loss of a loved one, but that doesn’t forbid the general public from celebrating his inability to cause further harm to marginalized groups. His program’s racism, xenophobia, misogyny, and general trivialization of real-world issues primed audiences for the polarizing cable news era, leaving Limbaugh somewhat culpable for the recent rise in alt-right politics. Like with so many other destructive, ignorant, and evil figures throughout history, it is wholly appropriate for Americans to celebrate and mock Limbaugh’s early death.