Opinion: Students Should Change Attitudes Around Annotations

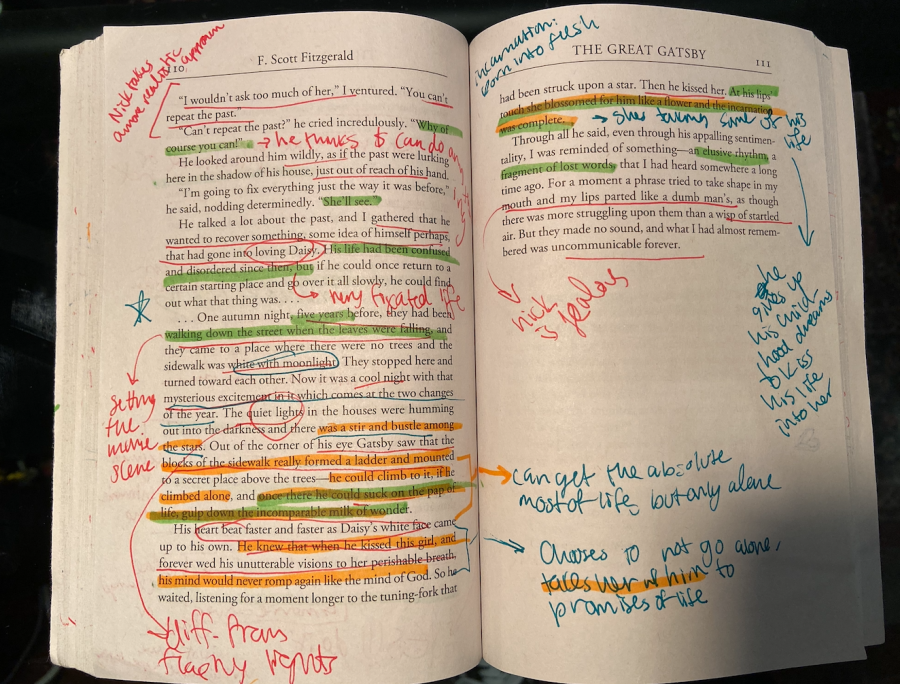

In Upper School English classes at Friends Select, even the slightest mention of required annotations generates exasperated moans from many students. The laborious task of meticulously underlining significant quotes and explicating notable passages is widely thought to consume excessive amounts of time and drain the joy from reading. Despite this inconvenience, teachers view annotations as a critical part of reading comprehension. Many students currently cover their pages in ink or graphite without retaining much information, but this does not mean that annotations should not be required; it means that teachers should explicitly teach students how to annotate productively and efficiently. If done correctly, the helpfulness of annotations should justify the time spent marking pages.

Although students may view annotations as a draconian method of ensuring that they complete required readings, these notes serve a real purpose. Thoughtful and deliberate annotations enable students to bookmark their favorite passages and identify central themes and motifs. When writing essays and reflections, annotations allow students to easily refer to useful quotes and literary patterns. One study published by the Cambridge University Press found that students who annotate display better recollection of the events, patterns, and greater meaning of literary texts. In 11th grade English teacher Suzanne Morrison’s eyes, “annotations are the building blocks of critical thinking and close reading in English class.”

Productive and worthwhile annotations are contingent upon students’ willingness to actually put effort into their reading. If students view annotations as an added chore, they will likely mark pages lackadaisically and view the process with disdain. Conversely, if they examine texts with real focus and intent, their annotations will reflect the big picture ideas present in a reading. A study from the University of Texas at Austin found that students who are taught how to annotate effectively can use those skills to aid their comprehension while reading. Instead of complaining, students should focus more on sparse and impactful notes to retain more information when they read.

Data collected from an Upper School survey indicates that students view annotations more favorably than the student body’s general attitude might suggest. 30% of 69 responding students said that compulsory annotations inhibit their learning, while 41% say that they benefit from the requirement. Although a fairly loud sect of the student population decries annotations as cruel and unusual punishment, there is little evidence to suggest that most students actually take issue with these assignments.

English teachers Suzanne Morrison, Miriam Rock, and Matthew Rosen all support the general idea of annotations. In their eyes, annotations encourage students to develop an intimate and nuanced understanding of books, leading to more thoughtful class discussions. Putting pen to paper can also make character traits more memorable and organize students’ thoughts before they are assessed on their analytical skills — as Suzanne says, “a stitch in time, saves nine.” Furthermore, annotations can help students save quotes for essays and other writing assignments: “Ideally, a student doesn’t have to flip through the novel, frantically looking for that quote that would be so good for the essay,” says Suzanne.

However, the teachers agree that annotations have some drawbacks. As Matthew notes, “one drawback is over-annotating, so that the annotations become unclear and diluted.” This year, Miriam does not require her students to annotate: “I’m trying it out this year to see if I can accomplish the same pedagogic goals with different kinds of assignments,” she says. Instead, she issues exit-ticket style prompts “to test their ability to analyze the text a few times per book.”

In order to make annotations worthwhile, English teachers should begin the school year by teaching their students how to annotate effectively. Many students dislike annotations because they currently consume copious amounts of time with little payoff. Improving students’ attitudes around annotations is a two-way street: students should be more open to annotating, but teachers should also be clearer in their advice and expectations.

Additionally, reading for pleasure and annotating are not mutually exclusive. “Reading for English class can and often is pleasurable, and in fact, annotating can make it more so, as it keeps you alert while you track patterns and appreciate technique,” says Suzanne. “I think students get frustrated with annotations at times because it takes extra time and because maybe they can’t just quickly read or lose themselves in the text. But, frankly, that’s the point. We want students to stay alert and focused during reading. We want them to become expert ‘pattern-trackers.’” Suzanne humorously recalls that when she read for pleasure shortly after completing her doctoral exams, she found herself struggling to resist annotating due to muscle memory.

Students at Friends Select are justified in wanting to fully appreciate the books they read in 9th, 10th, and 11th grade English. Texts like The Catcher in the Rye, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Things Fall Apart, and The Great Gatsby are some of the most enjoyable, thought-provoking books in literature, and students should be able to read them in the way that they can best understand. Contrary to what these students say, though, mandatory annotations do not forbid this. If students learn to value measured annotations as an essential part of understanding literature, they can simultaneously better enjoy their English classes and get more out of reading.

Peter Ryan is a senior at Friends Select School. He currently serves as President of Student Government, Co-Clerk of QUAKE, and founding leader of Cricket...